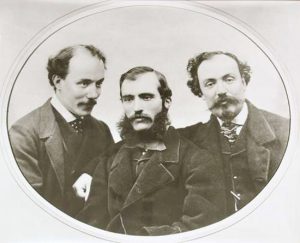

Leopoldo, Giusepppe e Romualdo Alinari, fondatori della Fratelli Alinari Leopoldo, Giusepppe e Romualdo Alinari, founders of Fratelli Alinari 1865, Archivi Alinari This file has been identified as being free of known restrictions under copyright law, including all related and neighboring rights Fonte: Wikimedia Commons

Fondazione Alinari per la fotografia: l’accordo con il MIBAC non sceglie l’open access

In un nostro articolo del 24 gennaio scorso “Cosa si può imparare oggi dal fallimento del modello di business dell’azienda Alinari?” avevamo scritto della Fondazione Alinari e del suo immenso archivio fotografico, manifestando preoccupazione per la volontà, espressa dal suo Presidente Giorgio van Straten, di mantenere un modello di business legato esclusivamente alla vendita delle riproduzioni digitali delle opere fotografiche e dei relativi diritti d’uso.

Ci siamo anche chiesti se fosse stato stipulato qualche tipo di convenzione con il Ministero dei beni culturali inerente l’utilizzo delle riproduzioni: a tal proposito, siamo a conoscenza della notizia di un accordo con il Mibac che va in direzione contraria rispetto alle istanze dell’open access.

L’accordo-quadro del 16 dicembre 2020 tra la Dg Musei e la Fondazione Alinari, della durata di 5 anni, tra le altre clausole prevede che tutte le fotografie Alinari che riproducono beni in consegna ai musei statali siano “poste in consultazione online a bassa risoluzione, non superiore a 480 x 480 pixel, e con marchiatura digitale visibile e invisibile e con espresso divieto di riproduzione”, con “l’indicazione dell’autore della fotografia e la dicitura che la riproduzione è avvenuta previa autorizzazione dell’amministrazione che ha in consegna il bene, nonché l’espressa avvertenza del divieto di ulteriore riproduzione o duplicazione con qualsiasi mezzo”. L’accordo inoltre specifica che il corrispettivo dovuto al Mibac dalla Fondazione per l’utilizzo delle immagini per finalità editoriali (libri, riviste, cataloghi, periodici, giornali, progetti espositivi, culturali), cartacee o digitali, dovrà essere corrispondente ad una percentuale ricompresa tra il 25% e il 35%, la percentuale sale al 30-40% per la produzione di specifici articoli commerciali, mentre per tutte le altre tipologie di riuso commerciale sarà necessario prevedere ulteriori accordi con il Mibac.

La convenzione stabilisce inoltre che l’utilizzazione delle immagini “dovrà essere compatibile con la destinazione culturale delle stesse, con il loro carattere artistico e/o storico, l’aspetto e il decoro del bene culturale riprodotto”, mentre rimarrà in capo al Mibac il potere di inibire l’ulteriore diffusione di immagini lesive del decoro e di richiedere un risarcimento per il danno eventualmente procurato.

L’obbligo di pubblicazione di immagini online solo a bassa risoluzione (con divieto esplicito di ulteriore riproduzione) associato alla previsione della corresponsione di un canone per la maggior parte degli utilizzi, avrà l’effetto non solo di ridurre drasticamente la libera godibilità e fruizione delle immagini di beni culturali pubblici in pubblico dominio, ma comporterà inevitabilmente un ulteriore aggravio delle tariffe sul riuso commerciale delle immagini. Ai diritti fatti valere dalla Regione Toscana per il tramite della Fondazione si aggiungeranno, infatti, i diritti imposti dallo Stato dovuti per la semplice raffigurazione di beni culturali statali sulle fotografie Alinari. Un doppio regime di diritti statali e regionali (per il tramite della Fondazione) graverà quindi sulle fotografie, tutto a danno dell’utilizzatore.

Sono diversi gli interrogativi che si pongono. Il canone sull’uso commerciale delle immagini è stato introdotto dalla legge Nasi nel 1902 (e stabilito dal Regio decreto 431/1904 che approva il Regolamento per l’esecuzione della legge sulla conservazione dei monumenti e degli oggetti d’antichità e d’arte che, d’altro canto, ricordiamo prevedere all’art. 243 la libertà di panorama, riconoscendo che “le riproduzioni fotografiche all’aperto delle parti esterne dei monumenti esposti alla pubblica vista, sono libere a tutti”).

Non dovrebbero allora essere liberamente riutilizzabili le fotografie scattate per conto degli Alinari prima di quell’anno?

Se ignoriamo questo limite allora dovrebbero essere sottoposte allo stesso tipo di trattamento anche le riproduzioni di disegni e dipinti che dal Rinascimento in poi, in tutto il mondo, ritraggono monumenti statali italiani?

Il codice dei beni culturali non opera alcuna eccezione in relazione alla modalità di esecuzione delle riproduzioni stesse. Che dire allora delle bellissime fotografie del Getty Research Institute che riproducono intorno al 1870 alcuni dei più bei monumenti di Roma, oggi in consegna al Mibac, e che sono rese disponibili dal museo per qualsiasi finalità, anche commerciale (http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/42880/gioacchino-altobelli-temple-of-vesta-rome-1871/)? Sarà forse il caso di citare il Getty per il “danno erariale” che ne deriva e di addivenire a una convenzione esemplata su quella stipulata con Alinari?

In definitiva questi paradossi indicano che i modelli del passato non sembrano voler cedere il passo a una visione che punta al riconoscimento delle potenzialità del digitale come leva imprescindibile di valorizzazione del patrimonio culturale e diffusione della cultura e della conoscenza. Sono i residui di un paradigma anacronistico che non si concilia con le esigenze di promozione e divulgazione delle riproduzioni di beni culturali pubblici in pubblico dominio, in aperto contrasto con la cultura del riuso che si sta diffondendo in ambito internazionale (Open Glam) e con quanto statuito dall’art. 14 della Direttiva 790/2019/EU sul copyright, in base alla quale tutto ciò che è in pubblico dominio (cioè fuori dal campo del diritto d’autore nel mercato unico digitale), deve rimanere in pubblico dominio. Tale approccio non intende escludere, come difatti non esclude, l’opportunità per gli istituti culturali di commercializzare prodotti editoriali, come la vendita di cartoline o gadget, merchandising, come il Considerando 53) della direttiva sopra indicata suggerisce.

Non possiamo far altro che auspicare un ripensamento della gestione dell’archivio in favore di un approccio che tenga conto delle infinite possibilità dell’Open Access e che si allinei con le tendenze ormai sposate da moltissimi istituti culturali nel mondo che vedono nella libera circolazione delle immagini una risorsa al servizio dello sviluppo complessivo della società.

Come scrive Michele Smargiassi su La Repubblica (16/02/2021) “fin dall’inizio le fotografie degli Alinari (…) non furono opere d’arte da contemplare, ma oggetti visuali da riutilizzare, materia prima riproducibile per gli scopi più diversi: libri, certo, ma anche cartoline illustrate, calendari, pubblicità, oggetti d’arredamento, gadget…”. Ciò è tanto più vero oggi perché, grazie alla duttilità del digitale e al suo potere trasformativo, il patrimonio finalmente pubblico di Alinari dovrebbe essere reso libero di reincarnarsi in una miriade di prodotti creativi: precisamente questa dovrebbe essere infatti la nuova frontiera del servizio pubblico. Altrove lo strumento flessibile della Fondazione si è rivelato utilissimo, all’opposto, per mettere in pratica ciò che nessun museo statale oggi oserebbe fare: è il caso, ormai celebre, del Museo Egizio di Torino che, solo grazie all’autonomia gestionale del museo stesso, ha potuto liberalizzare l’uso delle immagini di beni culturali, ancorché di proprietà Mibac, per qualsiasi fine, anche commerciale.

Eppure un barlume di speranza sembra, sia pur involontariamente, provenire dall’art. 6 della convenzione tra il Mibac e la Fondazione Alinari laddove si prevede che “il presente accordo si intenderà automaticamente modificato ed integrato” nell’ipotesi di entrata in vigore di nuove norme sull’uso delle immagini. Ebbene, il nostro auspicio è che la normativa di tutela possa ammodernarsi davvero, rimuovendo ogni ostacolo al libero riutilizzo delle immagini del nostro patrimonio culturale, al punto da permettere non tanto la modifica dell’accordo ma il suo stralcio in nome di un modo diverso, e più democratico, di intendere il rapporto tra cittadinanza, istituzioni di tutela ed eredità culturale. Sarebbe forse questo, in fondo, il miglior tributo al “decoro” della pubblica amministrazione e della Fondazione che si trova oggi a gestire uno dei più importanti archivi fotografici al mondo.

____________________________________________

ENGLISH VERSION

The Alinari Foundation: the Agreement with the Mibac denies Open Access

In an article of January 24th “What can we learn today from the failure of the Alinari business model?“, the CC Italian Chapter wrote about the Alinari Foundation and its huge photographic archives, showing concern for the desire expressed by its President, Giorgio Van Straten, to maintain a business model based exclusively on the sale of digital reproductions of the photographic works and the relative rights of use.

We also wondered whether any kind of agreement had been stipulated with the Ministry of Cultural Heritage concerning the use of reproductions: in this regard, we have become aware of agreement with the Ministry (Mibac) that goes against the open access instances.

The framework agreement of December 16th, 2020, between the Museums Department and the Alinari Foundation, with a duration of 5 years, provides, among other clauses, that all the Alinari photographs that reproduce goods on consignment to state museums must be “placed in consultation online at low resolution, not exceeding 480 x 480 pixels, and with visible and invisible digital branding and with an express prohibition of reproduction,” with “the indication of the author of the photograph and the wording that the reproduction was made with the prior authorization of the administration that has the goods in its care, as well as the express warning of the prohibition of further reproduction or duplication by any means”. The agreement also specifies that the fee due to the Mibac by the Foundation for the use of the images for editorial purposes (books, magazines, catalogs, periodicals, newspapers, exhibition or cultural projects), whether paper or digital, shall correspond to a percentage between 25% and 35%, the percentage rises to 30-40% for the production of specific commercial items, while for all other types of commercial uses it will be necessary to make further agreements with the Mibac.

The agreement also establishes that the use of the images “must be compatible with their cultural destination, with their artistic and/or historical character, and with the appearance and decorum of the cultural asset reproduced”, and the Mibac will retain the power to inhibit the further diffusion of images that damage decorum and to request compensation for any damage.

The obligation to publish images online only at low resolution (with explicit prohibition of further reproduction) associated with the provision of a fee for most of the uses, will not only drastically reduce the free use of public cultural heritage’s images in the public domain, but will inevitably lead to a further increase in the rates on the commercial use of images. In fact, in addition to the rights asserted by the Region of Tuscany through the Foundation, there will be the rights imposed by the State for the simple representation of the State’s cultural heritage on Alinari photographs. A double regime of state and regional rights (through the Foundation) that will have negative effects on the re-user.

Several questions arise. The fee on the commercial use of the images was introduced by the Nasi Law in 1902 (and established by Royal Decree 431/1904 “approving the Regulations for the execution of the law on the conservation of monuments and objects of antiquity and art” which, on the other hand, in art. 243 states the freedom of panorama, recognizing that “photographic reproductions of the external parts of monuments exposed to public view, are free”).

Shouldn’t the photographs taken on behalf of the Alinari before that year be freely reusable?

If we ignore this limitation, should reproductions of drawings and paintings of the Italian monuments from the Renaissance onwards, all over the world, be subject to the same type of treatment?

The Code of Cultural Heritage does not make any exception in relation to the way in which these reproductions are carried out. What can we say then about the beautiful photographs of the Getty Research Institute that reproduce some of the most beautiful monuments in Rome around 1870, on which the Mibac is the consignee now, and that are made available by the museum for any purpose, even commercial (http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/42880/gioacchino-altobelli-temple-of-vesta-rome-1871/)? Will it be necessary to sue the Getty for the “fiscal damage” deriving from this and to come to an agreement modelled on the one stipulated with Alinari?

These paradoxes indicate that the models of the past do not seem to want to give way to a vision that recognizes the potential of digital technology as an essential lever for the valorization of cultural heritage and the diffusion of culture and knowledge. This is an anachronistic paradigm that cannot be harmonized with the needs of promotion and dissemination of reproductions of public cultural heritage in the public domain, and that is in contrast with the culture of reuse that is spreading internationally (Open Glam) and with the art. 14 of Directive 790/2019/EU on copyright law in the digital single market, according to which everything is in the public domain (i.e. outside the field of copyright), must remain in the public domain. This approach does not exclude the opportunity for cultural institutions to market editorial products, such as the sale of postcards, gadgets, merchandising, as Recital 53) of the above-mentioned Directive suggests.

We can only hope for a rethinking of the management of the archives in favor of an approach that takes into account the infinite possibilities of Open Access and that is in line with the trends of many cultural institutions around the world that intend the free circulation of images as a resource for the development of the entire society.

As Michele Smargiassi writes in La Repubblica (16/02/2021) “from the very beginning the Alinari photographs (…) were not works of art to be contemplated, but visual objects to be reused, raw material reproducible for the most diverse purposes: books, of course, but also picture, postcards, calendars, advertising, furnishings, gadgets…”.

This is all the more true today because, thanks to digital technology and its transformative power, the public Alinari’s patrimony should be made free to rebirth in a myriad of creative products as a precisely new frontier of the public service. Elsewhere, the flexible instrument of the Foundation has proven to be very useful, on the contrary, to put into practice what no state museum today would dare to do: this is the famous case of the Egyptian Museum of Turin which, only thanks to the managerial autonomy of the museum itself, has been able to freely share the cultural heritage images, even though they belong to Mibac, for any purpose, including commercial one.

A hope seems to come, maybe unintentionally, from art. 6 of the agreement between the Mibac and the Alinari Foundation where it is stated that “this agreement shall be understood to be automatically modified and integrated” in case new rules on the use of images come into force.

Well, our hope is that the regulations for the protection of our cultural heritage can be truly modernized, removing every obstacle to the free reuse of its images, to the point of allowing not so much the modification of the agreement as its cancellation in the name of a different and more democratic way of understanding the relationship between citizenship, institutions and cultural heritage. Perhaps this would be the best tribute to the “decorum” of the public administration and of the Foundation, which today manages one of the most important photographic archives in the world.